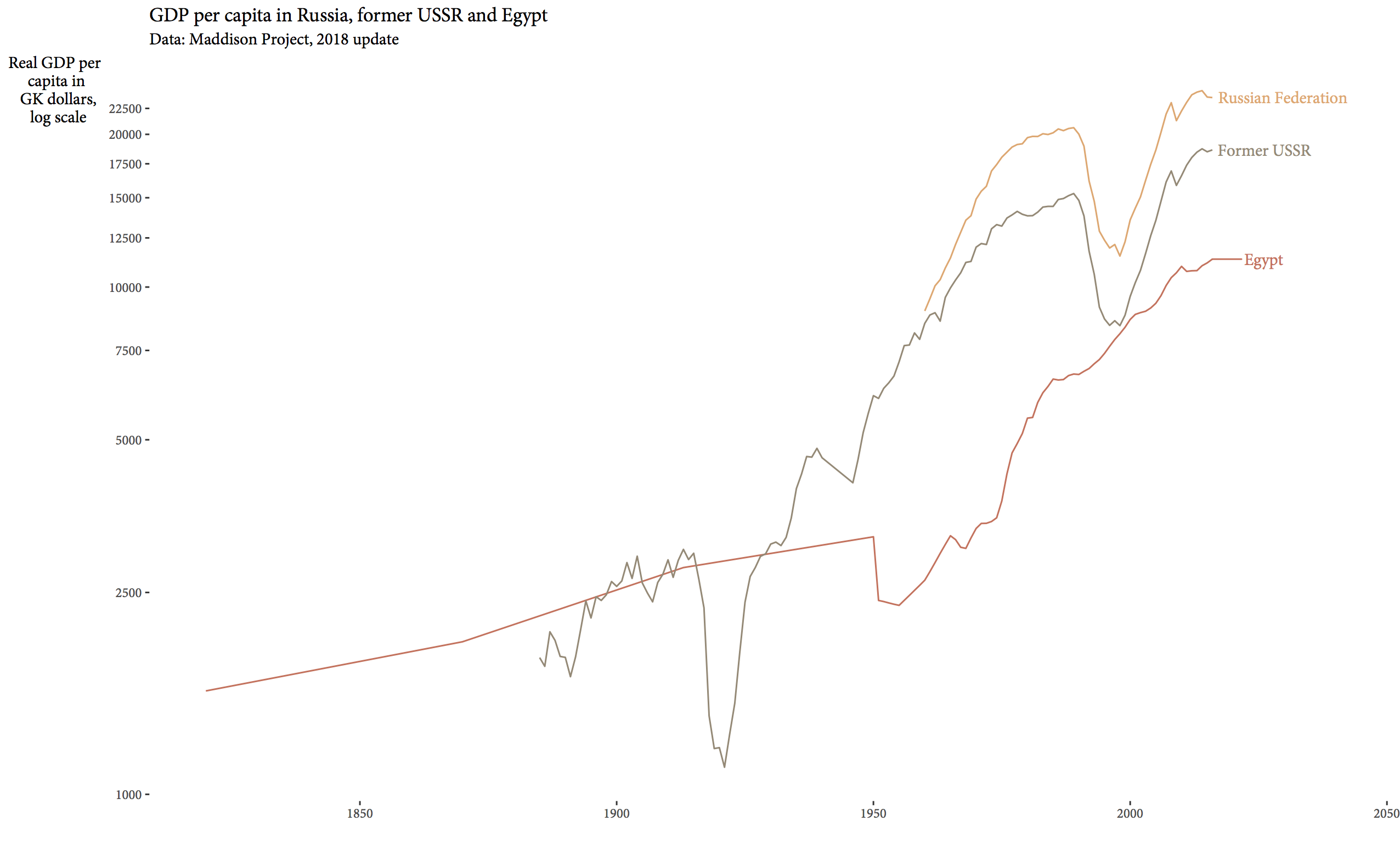

Neither Egypt nor Russia is Denmark, and you can tell because Egypt and Russia are in Group A in the World Cup and Denmark is in Group C. In the shorthand used by economic historians, however, in which “Denmark” is more adjective than noun—”why isn’t country X Denmark?“—the short answer is that neither Russia nor Egypt, despite considerable growth in the 20th century, is rich enough to be considered “Denmarkish”.

Not that they haven’t both tried very hard. Egypt, after all, was one of the first countries to look around itself, find itself not as prosperous as it wanted to be, and actively go about using the power of the State to get richer. As so often in the developing world, concerted industrialisation was centred around textile manufacturing: in the nineenth century, Egypt under Mehmet Ali Paşa 1 had as many cotton spindles per person as Spain (80 per capita), nearly as many as France (90 per person), and much more than Germany (22) or, especially, Russia (12). Russia famously got started late, but made up for tardiness with haste: before the East Asian Tigers and China got underway, Russia and its little archipelago neighbour Japan 2 were the only two really outstanding examples of countries that had discovered a workable get-rich-quick formula. It’s now fashionable—not to mention fun—to mock Paul Samuelson for his textbook’s prediction that Soviet per capita incomes would exceed US incomes, but the error was understandable. Soviet industrial growth really did look quite extraordinary to the mid-century observer, even if the price in blood was unforgivably high. (Of course, we have a lot more history to go on now; Soviet industrial growth looks nowhere near as impressive as it once might have.)

In both 19th century Egypt and 20th century Russia, the path to industrial growth was blocked by a formidable swamp: subsistence agriculture. Both Mehmet Ali Paşa’s government and Russian thinkers from Stolypin and Witte to Bukharin and Preobrazhensky were forced to confront a classic question of development economics: should we screw the peasants? For the peasant-screwing faction, which included Preobrazhensky and Mehmet Ali Paşa, this provoked subsidiary inquiries, such as: how exactly shall we screw the peasants? And how much shall they be screwed for?

First, a little painless theory. Why do the peasants need to be screwed, exactly? Industrialisation in a peasant economy requires certain things. In order to set up factories, you need machines, and you need to pay for the machines somehow. If you have state-led industrialisation, as in Russia and Egypt, then the easiest way to obtain money is by taxing people—the peasants, perhaps—or, equivalently, by imposing ‘marketing boards’ for agricultural output that buy food at artifically low prices and sell at higher prices. The agricultural surplus is made to pay for the capital required to launch state-led industrialisation.

What Mehmet Ali did was to impose an agricultural monopsony and food-retailing monopoly, buying up grain in the country at low fixed prices and selling it at high prices in the cities. The difference between low purchase price and high sale price was the state’s profit. Normally, this would have pushed up nominal wages in the factories, making manufactured goods expensive: except, as Laura Panza and Jeffrey Williamson argue, he owned the factories too, and so could impose real wage cuts on industrial workers. Thus both peasants (who received lower prices for their grain) and urban workers (who had to pay higher prices for that grain) were screwed to pay for the accumulation of capital required for industrial growth. In a famous article on the ‘price scissors’, Joseph Stiglitz and Raaj K. Sah argue that this was in fact necessary: the argument made by Preobrazhensky in the case of Russia—that you could screw the peasants and have industrial growth without screwing industrial workers as well—was untrue, since any attempt to turn the intersectoral terms of trade against the peasants by lowering grain prices would necessarily lead to excess demand for grain by urban workers. Equilibrium in the grain market could then only be restored by lowering factory workers’ nominal wages so they could afford less grain.

This result, of course, depends on the economy being closed at the margin; if grain can be imported, then the suffering of urban workers can be alleviated, albeit at the cost of lowering the surplus that the government has to invest in capital goods. On the other hand, Stiglitz and Sah agree with Preobazhensky’s more basic point: increasing the price of industrial output relative to agricultural output does mean the government gains a surplus it can invest in industry, and—perhaps counterintuitively—the more pissed off the peasants are (that is, the less they grow in response to lower prices) the higher the government’s surplus, because of the industrial-wage response just mentioned. At least up to a point.

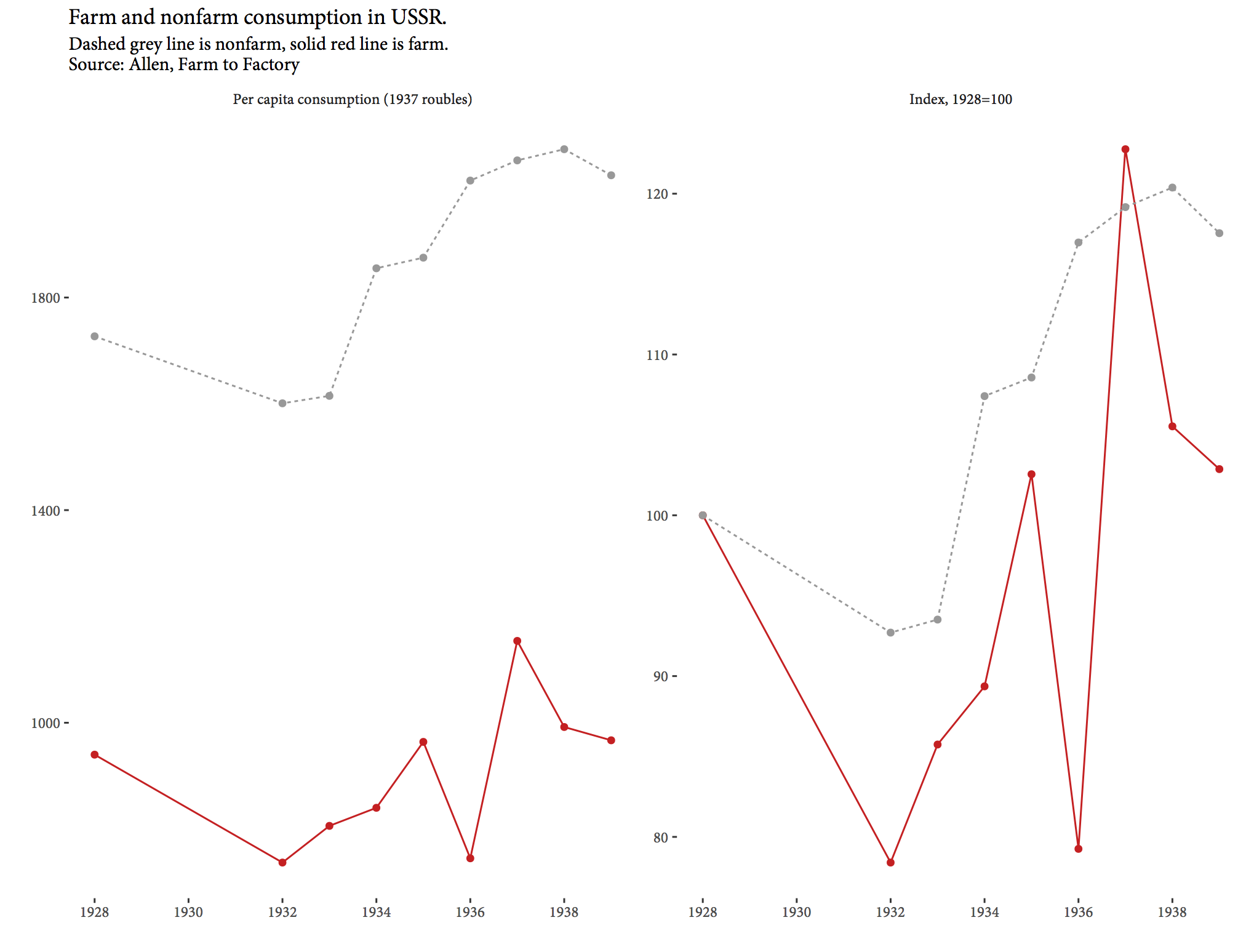

If we believe Bob Allen’s provocative economic history of Soviet Russia, however, a stagnant trend (albeit with high variability) in peasant consumption in the 1930s was combined with growing consumption in the cities, as you can see from the index presented in the figure above. However, as Allen points out (and this is a point I’ve made in relation to immigration and per capita income before) composition matters. The people who really got lucky here are the people who were farmers in 1928 and became industrial workers by 1939. A farmer who stayed on the land consumed about 3% more in 1939 than in 1928; a worker who had been in the city through that period consumed about 18% more at the end of that period than at the start. However, if you were a worker in 1939 who had been a peasant in 1928, then you were consuming, on average, 115% more than you were a decade prior. Put like that, it’s not surprising that so many people moved to the cities.

This bring us to another way to state the ‘food’ problem of the industrialisation state. You want the factory wage in terms of food to be high enough to entice people to move to the factories, but you also want the actual wage (in terms of dollars or roubles) to be low enough that what the workers are producing is made at a price low enough for people to want to buy it. Unfortunately for Mehmet Ali Paşa, even his firm grip on the hands of the ‘scissors’ was not enough to procure a viable textile industry, and most of the factories he had established were shuttered by the end of his reign. It’s traditionally argued that this was because the competition of Manchester flooded Egyptian markets with English cloth, although recently this has been disputed—after all, despite formal undertakings not to put barriers to trade, Mehmet Ali Paşa was able to use the purchasing power of the army to create a protected market for Egyptian cloth. Nonetheless, it would still be true that if Egyptian cloth were not price competitive with English cloth, then the prospects for industrialisation to fully satistfy home demand for textiles, let alone move beyond the import-substitution phase of growth, were limited.

Which is, of course, not to say that Mehmet Ali Paşa failed entirely as an economic steward. Indeed, his introduction of new crops, like long-staple cotton, arguably made the difference between a stagnant agricultural economy and one that grew substantially over the 19th century albeit less spectacularly than Russia’s would under import substitutiton industrialisation. That said, we still know much less than we would like about Egypt’s industrialisation and (?) deindustrialisation in the nineteenth century. As one of Egypt’s most famous footballers Mohamed Saleh (or am I confusing him with Mohamed Salah?) has argued, “there is still a wealth of unearthed primary data sources that could reshape our understanding of the [Middle East’s] history”. The goals, in other words, are wide open.