When the French parliament, including colonial representatives, was discussing the framework of a new relationship between French Africa and the metropole, a slight plaintive note could be detected in the contributions of the representatives of Côte d’Ivoire and Gabon. Respectively, these colonies were the largest economies of the federations of French West Africa (Afrique occidentale française, or AOF) and French Equatorial Africa (Afrique équatoriale française, or AEF). The white Ivorian planter Gaston Lagarosse said:

we think it necessary that those territories with the financial means ought to contribute to stabilising the budgets of less well-off territories that still fly the French flag, we nonetheless think also that this expenditure ought to be divided up among the whole of the French Union, including the metropole, instead of merely among the African federations, which are in any case groupings that are quite artificial and bring together peoples that are quite different from one another.

Luc Durand-Réville of Gabon said more or less the same thing:

the French Union for us means putting Côte d’Ivoire on the same level as [the former department] Côtes-du-Nord or the deparment of Aisne on the same level as Gabon. This is the context in which the solidarity of the French Union must be applied economically, socially and politically. Such solidarity in the French Union must exist, yes, but not within a single grouping of territories with arbitrary borders.

The complaint is about imperial inequality and the demand for redistribution. The French colonial federations in Africa were unequal, with some richer territories and some less well-off. For France, this provided the motivation for federating its colonies in the first place: rather than having to subsidise the poorer territories itself, it could call on the richer colonies, like Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal and Gabon, to do so. For Côte d’Ivoire and Gabon, however, this was unfair: if France wanted an empire, it should shoulder the cost of equalising incomes within it.

Some brief historical background: AOF incorporated eight colonies (clockwise from the northwest: Mauritania, Sénégal, Guinée, Côte d’Ivoire, Dahomey/Benin, Niger, Haute-Volta/Burkina Faso, and Soudan français/Mali). Depending on the context Togo is included, but because of its status as a League of Nations mandate, it was de jure separate from the rest of the AOF. The AOF was formed in 1895, but the actual establishment of federal political and economic infrastructure is usually dated from 1905, when the capital moved from Saint-Louis to Dakar and federal budgets were formulated. In the 1950s, various proposals for autonomy within the empire—or for independent federations that mimicked the structure of the AOF—were floated…and sank. By the early 1960s, all of the AOF colonies had become independent countries within their colonial borders.

It should be fairly obvious that economic inequality among the various parts of the empire was crucial to the politics of the last few years of colonial rule; moreover, it can, I think, help to explain why some of the grand projects for democratic imperial federalism, of the kind outlined by Frederick Cooper and Gary Wilder, failed to eventuate. And since Emiliano mentioned the work of Branko Milanović in his post, I think it’s a nice fit that Branko has done a lot of work on the economics of international federations and their collapse; I think it’s hard to understand the eventual collapse of Afrique occidentale française as a federal project without understanding the economic challenges of fiscal federalism. In fact, I have a working paper on this question in progress! In this post, though, I’ll focus not on the politics of imperial inequality and instead work on establishing just how unequal the AOF federation was, focusing on three separate questions:

Wages

One of the easiest way to compare one colony to another is to look at stuff that’s relatively conceptually easy to measure, like real wages, using the now well-known methodology of Bob Allen. This involves coming up with a ‘barebones subsistence’ basket of goods—the stuff that’s enough just to keep someone alive, not comfortable—and to calculate the basket’s price. Then you divide the nominal wage of a labourer by this basket price multiplied by three (assuming the labourer is also looking after a spouse and two children). We can then compare these ‘welfare ratios’ across time and across countries. As it happens, I’ve been working on creating such series for French West Africa; and, as it happens, as part of the new release of the Maddison database on per capita income (for more of which, see below), so have some other researchers. My work is nowhere near complete yet, but I picked a random year (1953) for which I’m pretty certain of the wages I’ve collected. The Maddison database working paper also presents urban real wages (expressed as a percentage of South Africa’s, but we can back out the original wefare ratios), for 1950. Both are presented below:

Welfare ratios in French West Africa, 1950 and 1953

| Maddison, 1950 | Me, 1953 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sénégal | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 2.0 | 3.5 |

| Haute-Volta/Burkina Faso | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| Soudan français/Mali | 1.0 | 2.1 |

| Dahomey/Benin | 1.2 | 2.1 |

| Niger | 1.0 | 1.4 |

| Guinée française/Guinea | 1.0 | 2.0 |

My wage estimates are a mostly a little higher than for the Maddison estimates. Partly I think this reflects the fact that there was fairly strong growth in the AOF in the early 1950s, and high nominal wage growth. Obviously, the main takeaway here is that Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire had high urban wages—not unrelated, they also had fairly large urban sectors, compared with the rest of the AOF federation. You can see this in both the Maddison wage estimates and mine. When it comes to the second tier economies—the ‘inner periphery’ of the AOF—my estimates diverge somewhat from the Maddison ones.1 For the Maddison authors, this inner periphery consists of Haute-Volta (Burkina Faso today): in Ouagadougou, wages were reasonably close to those in Abidjan and over half of those in Dakar. In my estimates, however, the ‘inner periphery’ is composed of Soudan français (now Mali), Guinea and Dahomey (Benin). My own figures fit my priors better than the Maddison ones do (which is not necessarily a good thing!), as I think that distance to the coast—and hence to coastal trade—probably explains a lot about urban welfare in West Africa. The existence of the Dakar-Niger railway (which actually terminates on the Niger river, in Mali, not in present-day Niger) also helps to explain why wages might have been higher in Soudan français, which is nonetheless a landlocked colony: it enabled fairly large towns like Bamako and Kayes to develop, with large-ish urban sectors. On the other hand, meat was fairly cheap inland, thanks to the existence of large cattle herds in the Sahel.

And my data comes largely from the official Annuaires statistiques (supplemented with some other sources); if the Maddison team has looked at archival material detailing actual market transactions in markets for goods and labour, their numbers may be much more accurate than mine. All in all, I think I’ll be a lot more certain about the contours of wage inequality in French West Africa after a long stint in the archives in Aix-en-Provence and Dakar later this year, but it’s reasonably clear that workers in the cities in Senegal and Cote d’Ivoire had the highest wages in Afrique occidentale française.

Here, by the way, are some photos from the Archives nationales d’outre mer of two late colonial cities, one on the coast, the other inland:

Abidjan

Niamey:

Per capita income

As I mentioned above, the team behind the Maddison Project Database recently released a new version of their database, with new estimates of GDP designed to facilitate cross-country comparisons of income. These estimates make use of multiple price benchmarks to compare prices of goods and services across countries, rather than simply doing the comparison once and assuming (or hoping) that relative price levels remain unchanged across countries.

For African countries, including the colonies of Afrique occidentale française, the Maddison team decided to derive new estimates of relative GDP per capita for 1950 by considering the relationship between real urban wages, urbanization, food demand, and agricultural productivity. On the first two, the authors can bring data to bear (real wages from papers like Frankema and van Waijenburg and Bolt and Hillbom and the archival work they have done for AOF; urbanisation from the World Urbanization Prospects data). For the second two, they are required to make some assumptions about the parameters.

The net effect of the new income estimates compared to the ‘old’ Maddison figures from the 2013 update is to reduce inequality between both the sample of African countries for which they have new income estimates as well as to reduce inequality between the colonies of AOF (excluding Mauritania, for which there is no new estimate).

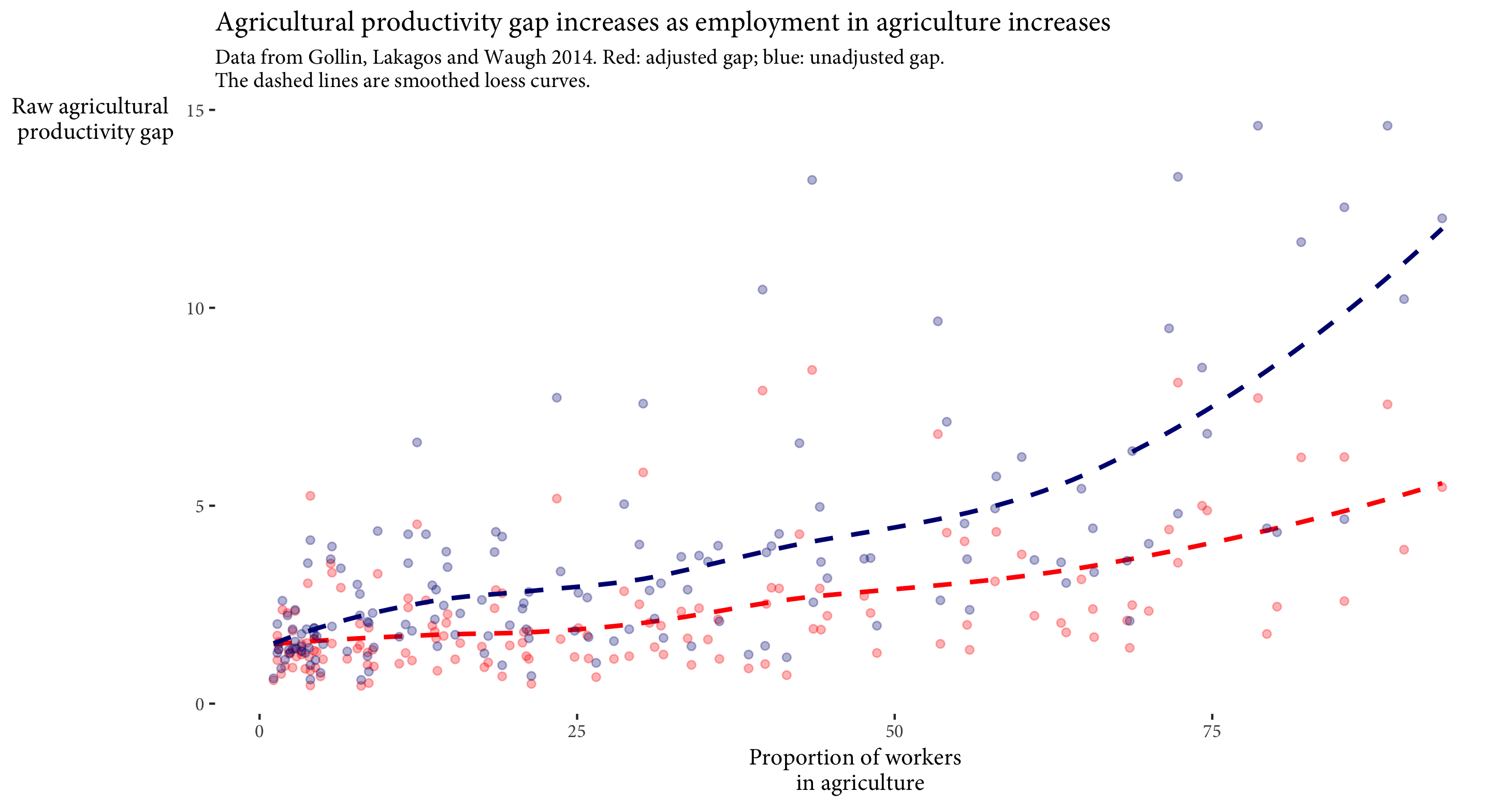

However, part of the reason for this compression of inter-colonial inequality is, in my opinion, the choice of a fixed parameter to express the difference in productivity between the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors (which I’ll just call the ‘productivity gap’). For all countries in their sample, this parameter in the MDP is 2, based on a paper by Gollin, Lakagos and Waugh. We can quibble about whether they picked the right number from that paper—I’d argue that maybe they should have picked a productivity gap of 3, since their choice of 2 is one that has been corrected for the different characteristics of agricultural workers, which we care about when we want to know about the intrinsic differences in the nature of both sectors, but not so much when all we want to know is how much stuff a worker produces in aggregate, for which we just need the raw, unadjusted productivity gap.

More fundamentally, though, if we’re interested in the inequality between colonies, it would be interesting to see what happens when we allow the productivity gap to vary between colonies. After all, in the Gollin, Lakagos and Waugh paper, it’s quite clear that the productivity gap varies enormously from country to country; the assumption that it was stable across African colonies is probably a little too strong. So how do we come up with varying productivity gaps? Well, the Gollin Lakagos and Waugh paper doesn’t help us greatly; their regressions don’t offer much in the way of explanatory power.

However, fortunately for us, they were trying to do something much harder than we’re doing: they were trying to explain productivity gaps; all we need to do is predict them. And to do that, we can actually use one of their other reported variables: the share of the population in agriculture, which is reasonably strongly correlated with the agricultural productivity gap. 2

When I do a simple OLS regression of agricultural productivity gaps on employment shares in agriculture using Gollin, Lakagos and Waugh’s data, I end up the following fitted equation:

Agricultural productivity gap = 1.3 + 0.08 * agriculture’s employment share

And since the Maddison estimates are already assuming that agriculture’s employment share is simply one minus the urbanisation rate, I can then use fitted values of the agricultural productivity gap to substitute in for the fixed parameter used in the Maddison estimates. This yields what I’ll call my ‘productivity-varying’ estimates of per capita GDP in AOF in 1950:

| GDP per capita: | Maddison (absolute) | Maddison (% of Senegal) | New (absolute) | New (% of Senegal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sénégal | $2343 | $2030 | ||

| Dahomey | $1217 | 51% | $777 | 38% |

| Haute-Volta | $1377 | 59% | $854 | 42% |

| Soudan français | $1292 | 55% | $924 | 45% |

| Côte d’Ivoire | $1746 | 74% | $1283 | 63% |

| Guinée française | $1227 | 52% | $830 | 41% |

| Niger | $1153 | 39% | $737 | 36% |

The changes are fairly dramatic, but the main impact of my new estimates is to distance Senegal from the other colonies in the AOF. The Senegalese city of Dakar was the capital of the federation, supporting a fairly extensive bureaucracy, and so the colony itself had a much higher rate of urbanization than any of the other colonies; mechanically, this means that its per capita income is assumed to be much higher than that of any other colony in the federation.

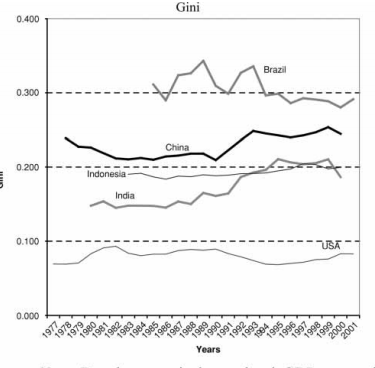

Per capita income Ginis (population-weighted) for country groupings in 1950

| Whole mini-sample | Afrique occidentale française | |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Old’ Maddison | 0.17 | 0.25 |

| New Maddison (income) | 0.11 | 0.16 |

| ‘Modelled’ gaps | 0.17 | 0.24 |

What does this mean? Well, it means that if we allow for varying productivity gaps, our estimates of intercolonial inequality in AOF are substantially revised: more or less all the way back up to the levels that the ‘old’ version of the Maddison database found. Much of this increase in estimated inequality is driven by the relative ‘pulling away’ of Senegal.

This has obviously important implications for the writing of West African political history. It also seems moderately interesting in understanding the possibilities for industrialisation in the periods before and after independence. If we take the Maddison figures, then Senegal’s share of AOF’s total GDP in 1950 was 20%; according to my revised figures, it represented 25% of total AOF GDP. According to the received wisdom, the loss of the West African market in 1960 largely doomed the nascent industrial sector in Dakar, forcing it to rely on the home market. There is no doubt something to this, but I think it’s important to quantify exactly how big the West African market was for Senegal.

We can compare these figures to other federations for which population-weighted inter-regional Ginis were calculated by Branko Milanovic: if we take the Maddison GDP figures, then the federation of AOF was about as unequal, in a regional sense, as India in the 1980s. If we take my figures, then it falls somewhere between ‘Chinese’ and ‘Brazilian’ levels of regional inequality:

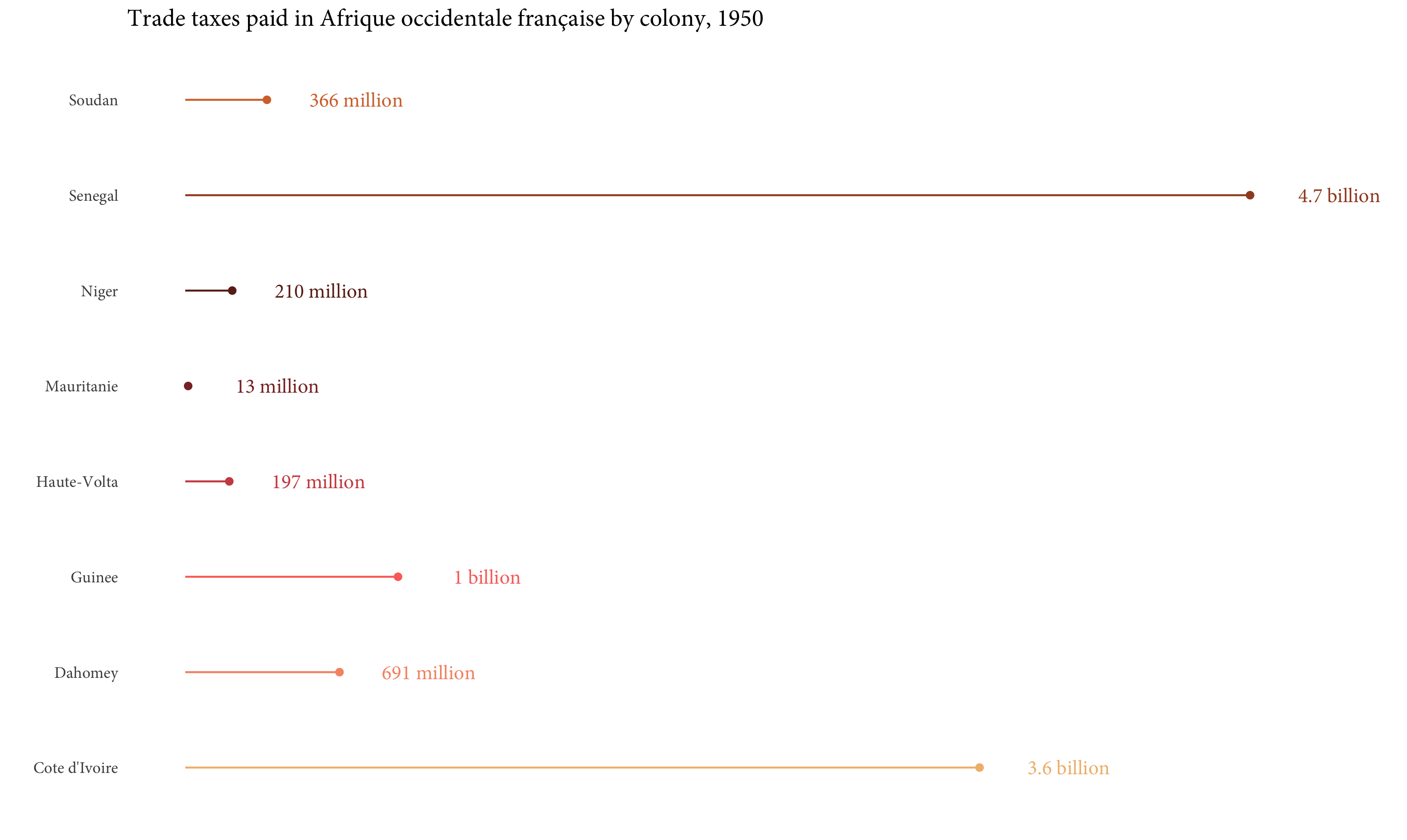

Taxes

The last metric on which we want to compare the economic fortunes of the constituent colonies of Afrique occidentale française is taxation, and it is federal taxation that provides the key to understanding the economics of federalist politics in the late colonial period, as the quotes as the beginning suggest. For the most part, AOF relied on trade taxes to fund its federal budget. This meant that, even though some trade was registered in the colony of destination (there were customs posts at Kayes in Soudan français, for example) much of the tax revenue for this budget was remitted by the coastal states, and especially Senegal (which, in the port of Dakar, had one of the best deepwater ports in West Africa, second only to Freetown) and Côte d’Ivoire.

Needless to say, as we saw at the beginning, the disproportionate burden of taxation falling upon the coastal states was a source of considerable angst for them:

| Colony | Trade taxes per capita per year |

|---|---|

| Mauritania | 13 francs |

| Haute-Volta | 46 francs |

| Niger | 64 francs |

| Soudan français | 99 francs |

| Guinée | 368 francs |

| Dahomey | 412 francs |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 1243 francs |

| Sénégal | 1796 francs |

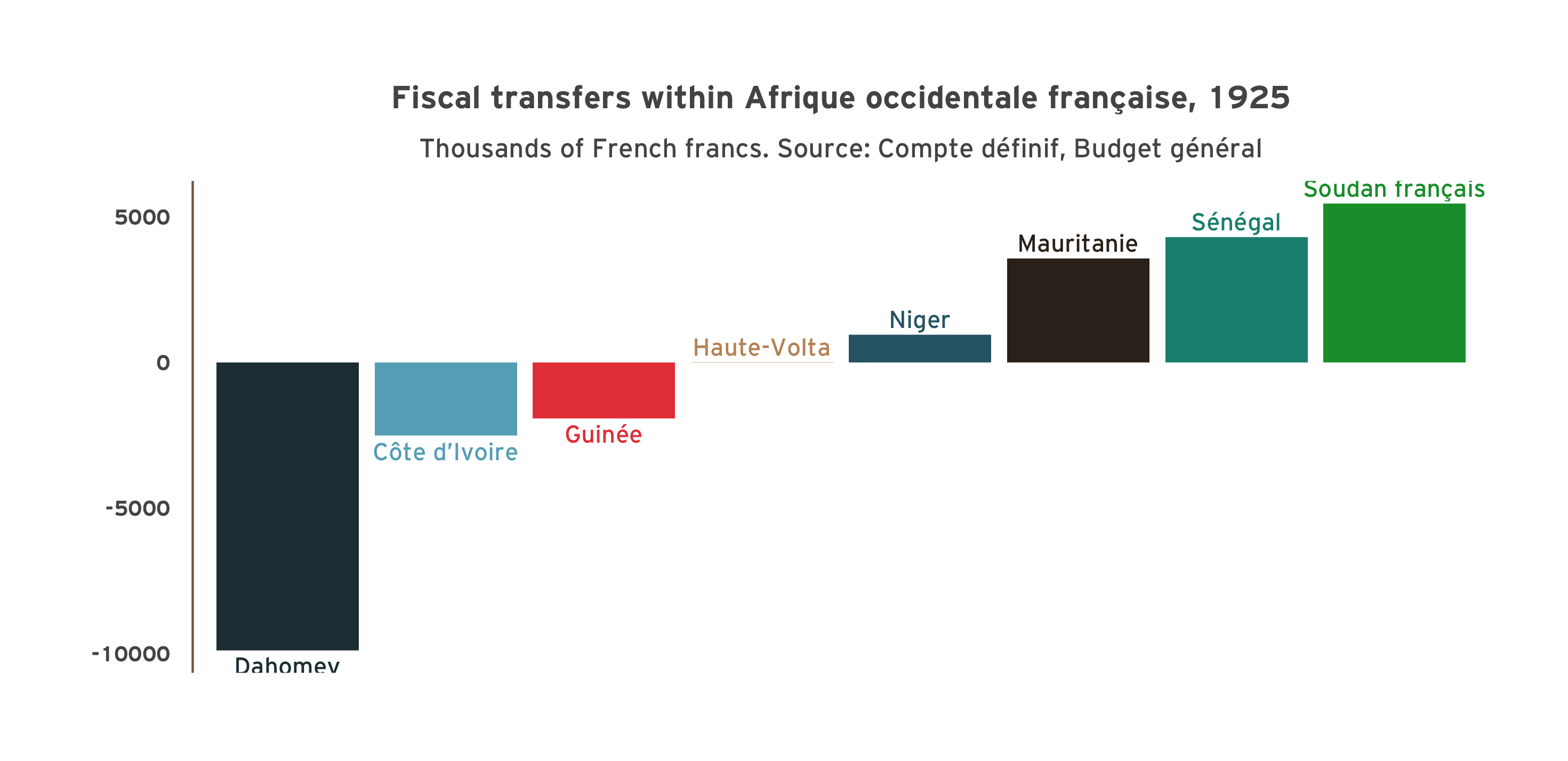

This was not, it should be stressed, the only way in which the ‘sand’ states like Soudan français and Niger contributed to the federal budgets: they also made lump-sum transfers from the other tax revenues they collected. We should also consider that federal spending was disproportionately concentrated on the same states that remitted most of the tax revenue, so the actual net fiscal impact was not quite the same: I also have a working paper in progress to quantify the fiscal transfers within the AOF over the course of its history. In the following chart, I show the absolute scale of these transfers—defined as federal spending minus federal taxes—for 1925, the year for which I have the most complete data:

The pattern, which was reasonably stable over the life of the federation, was that the coastal states, with the exception of Senegal, subsidised the inland colonies. Dahomey’s burden was largely taken over by Côte d’Ivoire later on in the period of federation. Senegal’s privileged position as a rich state that nonetheless received more federal spending than taxation was due to the location of Dakar, the federal capital, within Senegal’s territory; this ensured that federal spending outweighed federal taxation. I think this is a fairly obvious reason for Senegal’s relative enthusiasm for federalist projects just before independence, compared to the absolute reluctance of Côte d’Ivoire.

Conclusions

Whichever way you slice it, there was a considerable amount of inequality within the federation of Afrique occidentale française. My own estimates of GDP and wages suggest slightly more inequality than the more well-known estimates. I think the instability of the federation, and its collapse upon independence (as well as the failure of proposed successor states, like the Fédération du Mali) has a lot to do with this economic inequality. In future work, I hope to offer a model that uses some of the data I’ve covered in this post to explain the political economy of federalism in West Africa in the middle of the century.

- The fact that there is significant divergence for some countries when you compare across the estimates may be partly due to the fact that we’re looking at different years, but may also partly reflect methodology used to construct the subsistence baskets—when you use the Allen basket approach, you are sometimes forced to make choices about what to include in the basket (which grain is the cheapest? should we count pork as a protein option if most of the population of a city is Muslim and therefore won’t eat it?) [return]

- Presumably they didn’t incorporate this into their regressions because the employment share, like the productivity gap, is determined by more fundamental geographical endowments [return]