Economists don’t agree about the economics of dictatorships: some claim that the lack of checks on the executive and the widespread repression of political voice provide an institutional framework encouraging rent-seeking and stifling growth, whereas others think that it is precisely the lack of political accountability to the electorate that allows for economic policies that make technical sense and are conducive to growth but would not attain political consensus. Economic historians, whose job description allows them to focus on cases rather than on general rules, can point to examples supporting both theses (or neither). They could also try to reframe the discussion: from a wider human development perspective the choice between democracy and dictatorship should not be centred solely on economic growth. After all if democracy is desirable it’s because it makes us freer than other alternative regimes, not because it makes us rich (though some continue to argue that). On this post I’d like to focus on the distributional impacts of a ‘Structural Adjustment’ economic policy under a dictatorial regime, looking at the experience of the Latin American poster child for ‘free-market’ economic reform: Chile under Pinochet.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the Southern Cone economies (Argentina, Chile and Uruguay) had the highest per capita income in Latin America. Having reaped the benefits of the first globalisation boom, especially since the late 19th century and up to the First World War, they also led the region also in terms of manufacturing output per capita. This, in a context of rising incomes and massive European immigration, gave rise to strong trade union movements and early attempts at a welfare state. By the second decade of the century these three countries had universal male suffrage, and women were enfranchised before 1950. These developments contrasted with structurally high levels of asset and income inequality, and led to the election of candidates who made redistribution a central political issue. In Chile the government of the Social Christian Eduardo Frei Montalva (1964-1970) increased public investment in health and education, passed a land reform act, and encouraged the creation of new cooperatives and trade unions. The limits shown by some of Frei’s reformist policies encouraged the growth of more leftist political parties, who in 1970 won the national elections running together as Popular Unity (Unidad Popular, UP), with a Socialist presidential candidate, Salvador Allende, and the support of labour trade unions. Their platform centred on nationalising the mining industry (particularly copper, which accounted for two thirds of Chilean exports), the redistribution of income, the intensification of the agrarian reform already underway, and the improvement of working conditions, all as part of a ‘democratic transition to socialism’ – la vía chilena al socialismo.

When Allende came into office the international price of copper was on the rise, which meant that Chile’s terms of trade were extremely favourable and that fiscal revenue, linked to the copper industry via taxation and direct public ownership (about 20% of Chilean government revenue came directly from copper export production), was also increasing. Benefiting from that favourable international trade context, the government succeeded in further increasing public spending (which rose from c. 30% to over 40% of GDP), virtually achieving full employment and reducing income inequality. In 1972, remarkably high volatility in the international price of copper, together with rapidly increasing government deficit and debt as well as a poor manufacturing output, led to extremely high inflation levels that reached almost 300% the following year. Taking advantage of the environment of economic instability, the Chilean elite supported a coup staged on September 11, 1973 by a group of military high-ranking officers led by Augusto Pinochet. In the context of intense ideological confrontation brought about by the Cold War and with the (often explicit) support of the United States government, the Chilean military regime would remain in power until 1990. The National Congress was dissolved, political parties and labour unions were banned, tens of thousands of Chileans were tortured and killed and hundreds of thousands forced into exile, and the whole population lost the basic political rights of franchise, association and free speech. The return of democracy was led by the Coalition of Parties for Democracy (Concertación), an alliance of centre and centre-left parties, which arose from success in the referendum against the dictatorship in 1988 and remained in power until 2009.

The series of structural adjustment reforms under Pinochet were designed by a group of civilian economists: the Chicago Boys, Chileans trained as graduate students in the Department of Economics at the University of Chicago. In the late 1980s their economic program was hailed as a Latin American success story: when asked about the ‘Chilean economic miracle’ under Pinochet, Milton Friedman, who had taught the policymakers at Chicago, claimed that market forces in Chile had simply done ‘what Adam Smith said they would do’ and that the true miracle was that a military junta committed to a program of ‘bottom up economics.’ Against the background of Latin America’s ‘lost decade’ (as the 1980s became known as a result of economic stagnation and a region-wide debt crisis), Chile boasted rising export values, an average rate of GDP growth of 2.9% (although with high volatility), and a small but consistent fiscal surplus during the Pinochet years. Looking at the Chile in a slightly longer historical perspective, however, the real miracle is how fast income inequality increased during the dictatorship and how unable democratic governments have been to engineer a return to pre-Pinochet inequality levels.

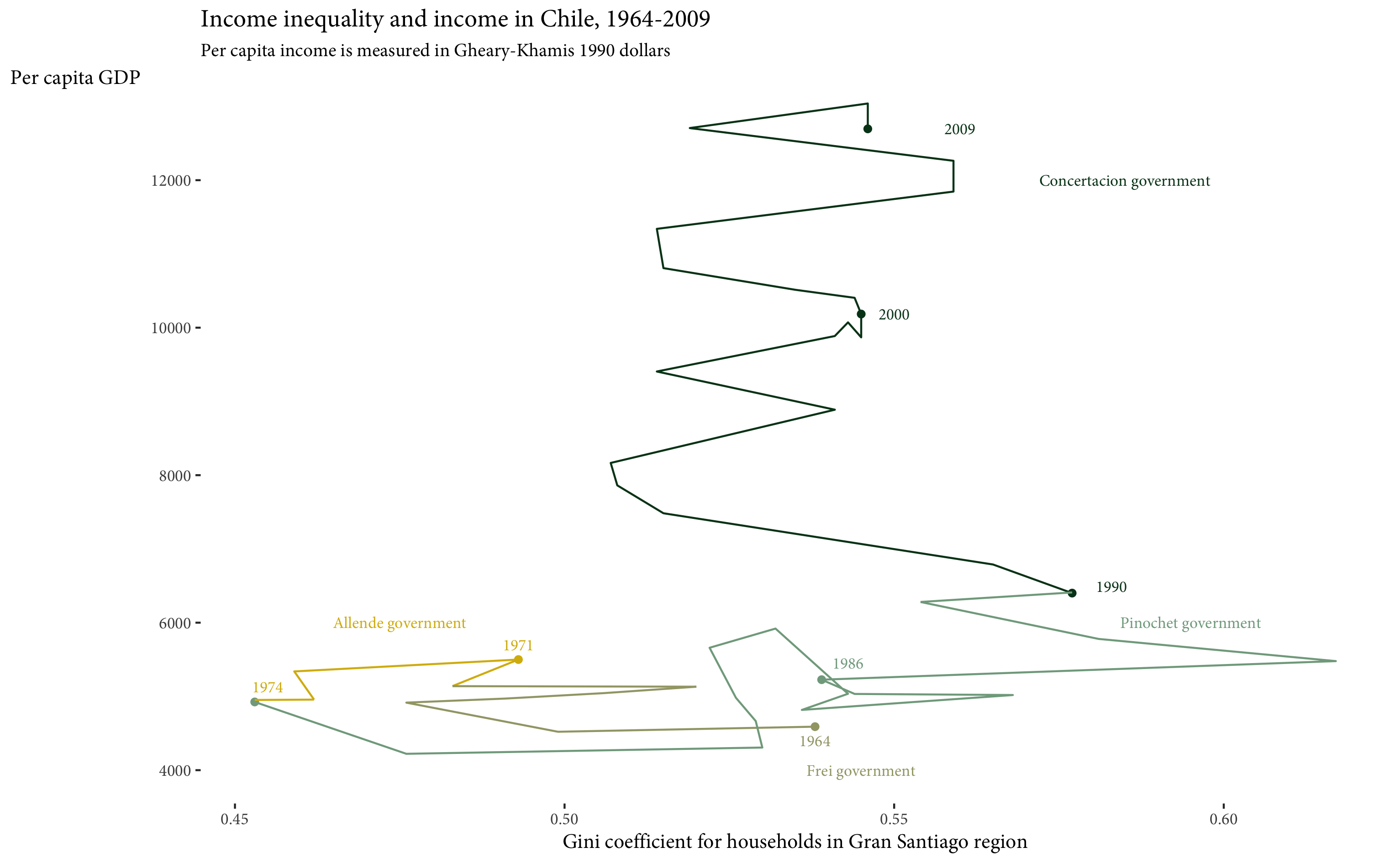

Source: per capita GDP: Montevideo-Oxford Latin American Database (MOxLAD); Gini: Universidad de Chile, Encuesta de Ocupación y Desocupación en el Gran Santiago, Santiago de Chile, 1964-2009. The Gini data available for the whole period refers only to the Great Santiago Area, but due to its population size and importance in the Chilean economy, it can be considered representative of the country as a whole.

The richest 20% of households in the greater Santiago area earned incomes 12 times higher than the poorest 20% when Allende’s government was violently put to an end in 1973. By the time Pinochet left power in 1989 that ratio had increased to 20:1. How did the Chilean dictatorship manage to so consistently increase already structurally high levels of inequality? The most convenient answer would perhaps be ‘by a systematic rolling back of the state’, but what happened was much closer to a radical reorientation of the state’s part in the economy than to its withering away. The copper industry remained largely nationalized (though the government revenue thereof was redirected towards security and defence), the national government continued to control labour relations (dismantling unions and preventing strikes), and when the privatizations of some national companies didn’t work out as planned the dictatorship was quick to re-nationalize them during the economic crisis of 1982. Friedman’s description of Pinochet’s Chile as the kingdom of ‘bottom-up economics’ was, it seems, rather naive. However, the Chicago Boys did unreservedly apply his teachings to some key sectors: health, pensions and education were opened to private companies and run (less explicitly but not less consequentially in the case of higher education) for profit, in what became one of the dictatorship’s most enduring legacies. The effects the privatization of the provision of public goods had on inequality were significant: operating in segmented and highly concentrated markets in a small economy prone to natural monopolies, the private health institutions, pensions managers and universities have become powerful economic actors in Chile.

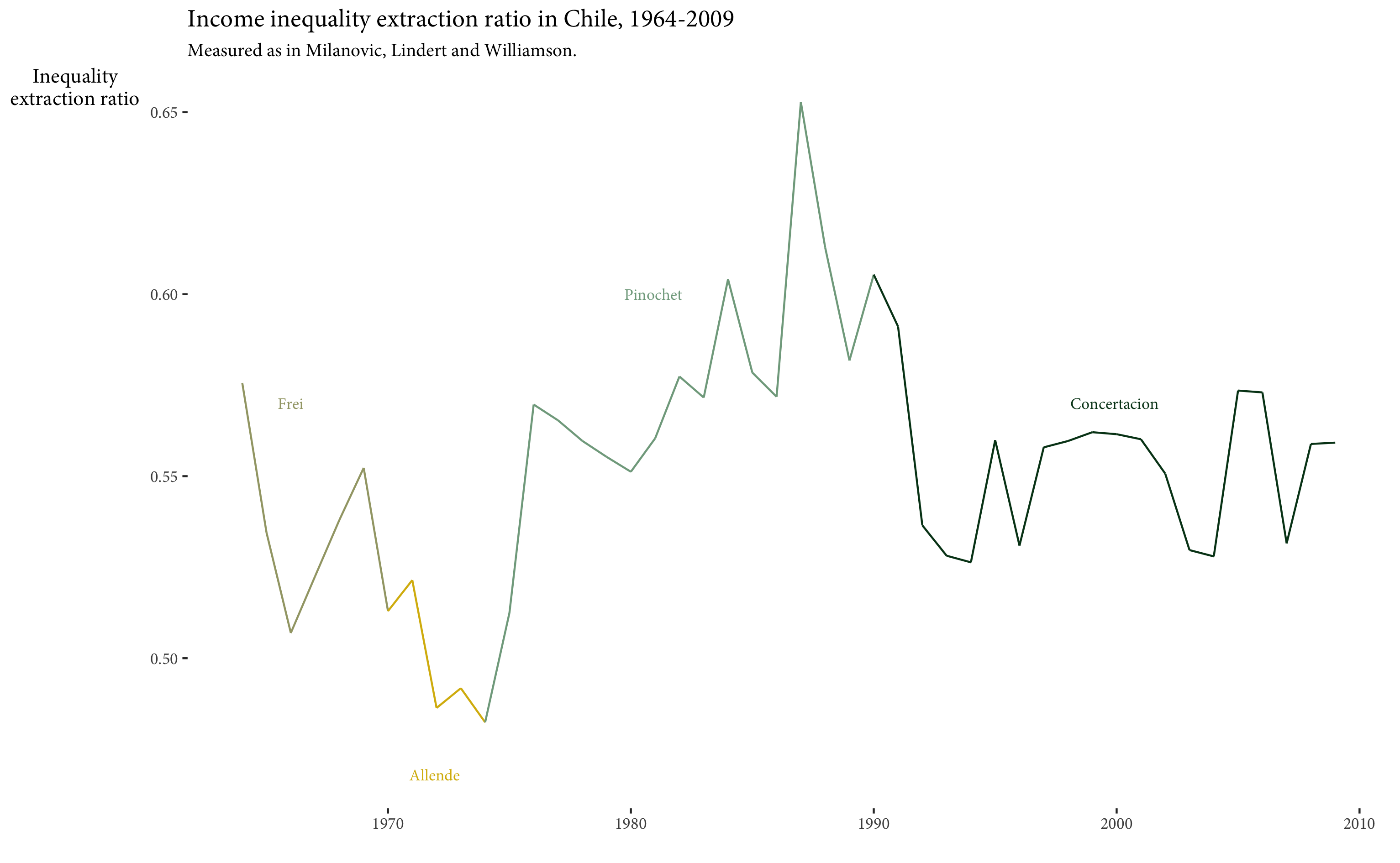

These policies, together with the effects of the dramatic fall of the international price of copper (which halved during the Pinochet regime), resulted in something that could be called a ‘Chilean miracle’: inequality increased at a much faster pace than output and average incomes, in a dynamic somewhat reminiscent of pre-modern settings. The rise in the inequality extraction ratio offers one measure of that process. Following Milanovic, Lindert and Williamson the inequality extraction ratio is calculated as the quotient between the Gini coefficient and the maximum feasible Gini (i.e. the inequality possibility frontier) in a given economy. The maximum feasible Gini takes a minimum annual subsistence income of s=300 Gheary-Kamis 1990 USD Dollars, and then calculates the distribution Gini assuming that everyone’s income is s except one individual who gets all the rest: that situation defines the inequality possibility frontier.

Source: GDP data from the Montevideo-Oxford Latin American Database (MOxLAD) and Gini data from Universidad de Chile, Encuesta de Ocupación y Desocupación en el Gran Santiago, Santiago de Chile, 1964-2009.

Income inequality increased almost everywhere else in Latin America, and indeed around the world, in the 1970s, so the Chilean trend under Pinochet should not be surprising. But the resulting inequality levels in the 1980s were extraordinary for a middle-income country, even for a Latin American one. They also proved persistent: in 2017 Chile was, together with Uruguay, the only Latin American economy classified as a ‘high income country’ by the World Bank, and yet in terms of income inequality it remains, with Brazil, the worst in the region. Latin American countries are generally much more unequal than expected according to their income, and Chile since Pinochet (and with no end in sight) is the most extreme case. When considering the economics of dictatorships distribution should be focused on as much as growth.

For more on Chilean inequality see this post by Javier Rodríguez Weber, translated and annotated by Pseudoerasmus; and for more on the economics of Latin American dictatorships read Joe Francis on Argentina. Stay tuned for ramblings on Latin American economic history, next time probably about Fray Bentos corned beef.